- Home

- Allen Steele

The Last Science Fiction Writer Page 18

The Last Science Fiction Writer Read online

Page 18

I glanced at Jen. She was in the passageway behind us, floating upside-down as she peeled out of her sweaty skinsuit. We gave each other a look, then I told the pilot I’d take it in the wardroom. He nodded, and I squeezed past Jen to the closet-size compartment just aft of the cockpit.

Mister Chicago was waiting for me there, a dollsize hologram hovering an inch above the mess table. He was seated in lotus position, naked from the waist up, his dead-white skin catching some indirect source of light behind him. His pink eyes studied me as I moved within range of the ceiling holocams.

“I understand you destroyed my casino today,” he said.

“Yes, I did,” I replied.

Rumor had it that Mister Chicago made his base of operations somewhere out in the belt, within an asteroid he’d transformed into his own private colony. If that was so, then he couldn’t be there now, because he nodded with barely a half-second delay.

“And I also understand that you managed to steal…” He brushed his shoulder-length hair aside as he turned his head slightly, as if listening to someone off-screen. “Six hundred and eighty megalox from my casino before you detonated a nuclear device within it.”

“Six hundred eighty million, seven hundred fifty thousand.” I shrugged. “I haven’t checked the exact figures, so there may be some loose change…yes, I did.”

“Well done, sir. Well done.”

“Thank you. We aim to please.”

To this day, I still don’t know exactly why Mister Chicago hired us to rob his own casino and then blow it up. Perhaps it had become a liability. Nueva Vegas was an expensive operation, after all; it may have cost more to keep it going than it brought in, and once its bottom line slipped from the black into the red, he may have decided to torch the place, once he’d made sure that he’d recovered every lox he could. He’d gone so far as to supply all the information we needed—JoJo’s nuke, schematics of the Nueva Vegas’s sublevels and gaming areas, the codes to disable the security ’bots and provide direct access to the DNAI—and even furnish a means of escape.

Yet even a gangster has to answer to legitimate underwriters: insurance companies, banks, investors, the Pax Astra itself. So what better way to cover himself than have his property nuked during a heist? If his scheme was successful, he could always claim someone else did it. And if it failed…well, I doubt our conversation would have been so pleasant. If it happened at all.

But that’s just my theory. Not for me to ask the reasons why.

“No lives lost, or so I’ve heard.” His right hand briefly disappeared beyond camera range; when it returned, it held a glass of wine. “Quite professional. I’m satisfied, to say the least. Add…oh, shall we say, another one percent to your take. Is that good for you?”

We’d agreed to do the job for five percent of whatever we managed to grab. A bonus was unnecessary, but welcome nonetheless. I felt a tap on my shoulder; looking around, I saw Jen hovering over my shoulder. She smiled and nodded. “Thank you,” I said. “Yes, that’s quite acceptable.”

Jen kissed my ear; I gently pushed her away. “Well then, I believe our business is concluded,” Mister Chicago said. “If I ever need your services again…”

“You know where to find us.”

“Very good. Thank you. Goodbye.” A final wave, then his image faded out. I let out my breath, turned around to find Jen behind me.

“Want to know what six percent of six hundred eighty megalox is?” she asked.

“Um, let’s see. That would be…” I shrugged. “You do the math. I’m busy right now.”

She grinned, moved closer to me. I reached out, shut the compartment hatch. Until the freighter reached the nearest Lagrange station, we had a long ride ahead of us. And we still hadn’t opened the bottle of wine she’d stolen.

WORLD WITHOUT END, AMEN

The last pessimist stood on a hotel balcony and contemplated suicide.

The lights of Boston stretched out before him: the elegant spires and helixes of glass, marble, and steel of downtown, the black expanse of the Charles River discernible beyond the antique brownstones of the Back Bay area. Looking down, he saw cars silently moving along Boylston Street; taxis stood in line in front of the hotel, while across the street a handful of pedestrians strolled through the Commons, taking in a warm summer night scented with lilacs and roses. He imagined lovers strolling hand-in-hand past its ponds and gardens, unafraid of the darkness, and somehow this made him even more miserable.

He turned away from the railing, shuffled back inside to pull from a pewter ice-bucket the bottle of champagne a room-service waiter had delivered a little more than an hour ago. Dom Perignon ’10: he’d deliberately picked that year, for it represented a happier time. He sloppily poured himself another drink—ignoring the pale gold drops that fell upon the pages of the speech he’d delivered earlier this evening, now scattered like dead leaves across the thick white carpet—and bolted it down as if it was a shot of cheap whisky. Champagne of this vintage was far beyond his means, as was this room, yet when he’d made the reservation, there had been a notion, somewhere in the back of his mind, that his life was coming to an end. There was just enough money in the bank for a one-night stand in a four-star hotel; if he wasn’t planning to live long enough to worry about paying bills again, he might as well indulge himself.

“‘Drink to me, drink to my health…’” The last words of Dylan Thomas, or perhaps a line from an old Paul McCartney song; either way, he couldn’t remember how the rest of it went.

The phone rang. He stared at it for a moment, teetering on his feet, indecisive of whether to answer it. It kept ringing, though, and at last he lurched over and picked it up. “Hello?”

“‘You know I can’t drink anymore.’” The voice on the other end of the line was perfectly modulated, without accent. “Perhaps you should lie down, Lawrence.”

Alfred. Of course, it was Alfred. All-seeing, all-hearing, omniscient…“Get bent,” he rasped, then slammed down the receiver.

Yet Alfred wasn’t finished with him. “You shouldn’t be doing this,” it said, and now its voice came from the phone’s external speaker. “If you like, I can order a pot of hot coffee…”

He reached behind the desk and yanked the cord from the wall, then staggered out onto the balcony once more. The city was quiet, a vast organism murmuring to itself as it settled in for the night. Hearing a low drone from somewhere overhead, he looked up to see the lights of an airship slowly cruising above the city. A commuter flight from New York or Washington, making final approach to Logan Airport on the other side of the bay. A long time ago, when he’d been in demand for speaking engagements, he’d traveled first-class, riding in the front cabin of airliners that farted vast ribbons across the sky. Today, he couldn’t even afford a seat on a short-haul blimp; he’d made the trip from Albany on a maglev trains, forced to share the company of blue-collar workers, housewives, and students…

Students. Like those in the audience tonight. Shutting his eyes, he clutched the burnished aluminum rail. They’d laughed at him…

“Lawrence, I really don’t think you should be out there.” Alfred’s voice came to him through the open door; now it spoke from the TV in the oak cabinet in front of his bed. “You’re depressed, and you’ve had too much to drink. Come back inside, please. You need…”

“Shut up, Red.” No, they hadn’t laughed. They were much too polite to do that. Yet when he’d glanced up now and then from the podium, the knowing smiles and quiet nods with which his words had been received in better days were gone, replaced by amused smirks and raised eyebrows; as he spoke, he heard the soft scuffling of feet, the occasional muffled apology, as someone quietly excused themselves, and each time the door at the back of the lecture hall banged shut it felt like another stake was being driven into his heart. And so sweat had oozed down his face and his voice had faltered, his tongue stumbling over words that he’d once uttered with conviction, again and again, in the course of a long and once-luminous

career, now no longer believing them himself yet forced by burden of reputation to proclaim once more. When he finally reached the end, the applause had been faint, and the moderator—a former colleague who’d once been a champion of his work, and who’d set up this speaking engagement to put a few dollars in the pocket of an old friend—mercifully declined to have the customary question-and-answer period. Which was just as well, for by then the hall was nearly empty, the seats filled only by a handful of undergraduates and a few faculty members who’d come in the same spirit of morbid curiosity that once compelled people to slow down on the Mass Pike to stare at car crashes. Back when cars used to crash, that is.

The champagne suddenly tasted like cold urine. Scowling in disgust, he tossed the glass over the side. It briefly reflected the lights of the hotel windows below him as it tumbled downward, then vanished from sight. He waited, and a moment later he heard the faint sound of it shattering upon the sidewalk, fifteen stories below.

“That posed a potential hazard to anyone who might have been down there.” Alfred’s voice expressed reproach. “I’ll have to report this incident to the hotel management, and also the police.”

“You do that.” Enough self-pity. If he was going to do this, he might as well get it over. Grasping the railing, he tried to pull himself over it. It was just a little too high, though, and he was drunk; his right knee slipped off and he fell back. Cursing under his breath, he looked around for something to stand on.

“Please don’t do this, Lawrence.” Alfred’s voice remained calm, yet there was an undertone of pleading. “There’s no reason for you to…”

He slammed the balcony door shut, then pulled a chaise lounge over to the railing. It wobbled a bit beneath his feet, but he had little trouble using it to climb over the railing. One leg at a time, he carefully stepped onto the narrow ledge, grasping the railing with slick hands as the toes of his shoes projected out over empty space.

“Sure, there’s a reason,” he murmured. “It gets me away from you.”

And then, without giving himself a chance to reconsider, he closed his eyes, spread his arms apart, and flung himself into the night.

“Dr. Kaufmann? Lawrence? You have a visitor.”

He didn’t look away from the windows as the nurse spoke to him from the door of the solarium. A steady rain had fallen all morning, shrouding the wooded grounds of the psychiatric wing with a fine grey mist, yet shortly after breakfast he’d asked an orderly to wheel him out here, as he’d done every day since he’d been admitted. He sighed, and closed the magazine that had rested in his lap, unread, for the past couple of hours.

This would have to happen. Might as well get on with it. Yet he said nothing, and after a second or two he heard the nurse murmur something to someone else. Heels clicked across black-and-white tiles, came to a stop beside him.

“Dr. Kaufmann? I’m…”

“The new shrink. Of course.” He lazily turned his head to look up at her. Late thirties, perhaps early forties. Casual business suit. A bit plump but otherwise easy on the eyes. Long brown hair tied back in a bun. A pleasant face, not beautiful but pretty all the same, with sharp aquamarine eyes that studied him from behind stylish wire-rim glasses. “What took you so long?”

“Not one for small talk, are you?” A professional smile.

“Oh, no. I’m great for small talk.” He surrendered to the inevitable. “Pick a subject. The weather’s lousy. The Red Sox are having a good season. The president is getting divorced. Another Mars expedition is about to return home. I jumped off a hotel balcony last week and all I got to show for it is this.” He patted the plaster cast that held his right leg immobile from the hip down past the knee. “Let me guess which one do you want to talk about.”

She found a chair next to a card table, pulled it over beside him. “The rain’s going to stop soon,” she said as she sat down. “The Sox lost last night’s game with the Yankees at the bottom of the eighth. The president’s marital problems are her own business, and I hope Ares 3 gets home without any more problems. Guess that eliminates everything else.” She extended her hand. “Melanie Sayers, and what took me so long is that I was vacation until yesterday.”

He ignored her hand. “You came back because of me?”

“You wouldn’t cooperate with the staff psychologists, so they decided to call in a specialist.” Melanie withdrew her hand. “Don’t worry about it. The Bahamas are boring.”

“I wasn’t going to.” He gazed at her long and hard. No bullshit, or at least so far. A good sign. “Doesn’t your case-load keep you busy?”

“Only sometimes. Not that many people attempt suicide these days.”

“You’re honest, at least.”

“Why shouldn’t I be? Besides, I don’t get many jumpers, so this is almost a treat. The suicide rate has dropped…”

“Twelve percent in developed countries in the last ten years, five percent in undeveloped countries. Twenty percent in the U.S. alone.” Lawrence gazed out the floor-to-ceiling windows, watching the rain scurry down their broad panes. “Of course, those figures only cover completed suicides. They’re probably different for ones made from hotels not equipped with fire-escape nets.” He paused. “You know…sensors in the outside walls detect a mass the size of a falling body, raises a sticky net. Body falls into it and another life gets saved…unless, of course, you happen to come down the wrong way, then something gets broken. Think I should sue?”

“I’m not a lawyer, but I wouldn’t advise it. Besides, if you’re so smart, then why didn’t you pick a hotel that doesn’t have that kind of equipment?”

“Never occurred to me. All I was looking for was a place with a good bar, room service, and outside balconies.”

“All you had to do was ask Alfred. Here, let me check.” Melanie reached into her jacket, pulled out a datapad. Flipping it open, she typed in her PIN. “Alfred, which hotels in Boston don’t have fire escape…?”

“Don’t do that.” Lawrence felt a muscle in his broken leg involuntarily twitch.

“Do what? I’m just asking Alfred for…”

He reached forward to snatch the pad away from her. “Go to hell, Red,” he said to it, then he snapped the pad shut and handed it back to her. “Don’t do that again. Next time I’ll throw it through the window.”

Melanie put the pad in her pocket, then raised her head. “Alfred?” she said, as if speaking to the ceiling. “Can you hear me?”

Silence No. Alfred.

“That’s one thing I like about this place,” he said. “You know it was built in the late 1800’s? It’s been refurbished, of course, but for some reason, no one thought to wire the sun room for wi-fi.”

“And you like that.” Not a question.

“If I thought it’d keep me from ever hearing him, I’d stay here for the rest of my life.” Lawrence forced a grin. “Look, lady, I’m crazy. Trying to kill myself just proves it. Do me a favor and sign the commitment papers. Food’s lousy, but…”

“Attempting suicide doesn’t mean you’re mentally ill. Depressed, yes, but depression is not the same as…”

“You wouldn’t say that to Napoleon.” He made a mock-solemn face as he tucked a hand into his robe. “‘Able was I, ere I saw Elba.’”

“Oh, please…” She pulled out her hand again, opened it and punched up a file. “Dr. Lawrence Kaufmann, Ph.D., Degrees in cybernetics and sociology from MIT and Harvard. Former vice-president of research and development at Lang Electronics. Author of…” She peered a little more closely at the screen. “Deus Irae: The Threat of Artificial Intelligence. Hey, I know that book.”

“Read it?”

“Sorry, no. I prefer history and biographies. But my husband did.”

“Ah.” Lawrence gazed out the window. As she’d predicted, the rain was letting up. “Well, then, you can tell him you met the author.” He paused. “As if he’d care.”

“He might. It was a bestseller, wasn’t it?”

“A long time ago.”

He knew that she was trying to lure him in, using conversational tricks to relax his defenses, and yet he didn’t care. At least she wasn’t as clumsy about it as Dr. Wychowski, whom he’d finally told to go away. Besides, he was in a mood to chat. “Put me on the talk-show circuit for awhile,” he went on, letting himself boast a little. “I used to be in the Rolodex of every network news producer in the business. Hell, I was in both Newsweek and Time the same week.”

“Guys who write novels about killer sharks do talk shows.” She tapped at her pad again, studied the screen. “No family history of mental illness, at least as far as I find here, but I haven’t…”

“If you step out into the hall,” Lawrence said quietly, “you can ask Alfred to do a full search. I’ll give you the names of my relatives and in-laws. But you won’t find anything new. No one in my family is crazy…except maybe me.”

“You’re not crazy. You’re…”

“Suffering from depression. You said that already. But if you’ve read Deus Irae…sorry, I meant if your husband has…and if you know I can’t stand to be around Red, then you know there must be something wrong with someone who doesn’t ever want to communicate with…it…ever again.”

“Maybe. Want to talk about it?”

He considered the question. If he didn’t talk to her, then they would only send someone else, and the next psychologist might not be as forthright as this one. And as comfortable as this solarium might be, he knew he couldn’t remain here indefinitely. Sooner or later, he’d have to confront the world again. Alfred’s world…

“Think you can push this thing?” He patted the arm of his wheelchair. “I’d like some fresh air.”

She hesitated. “I’ll have to get an orderly…”

“Ask for Raoul. Nice guy.”

“Raoul, sure.” She stood up. “But if we go out…”

Labyrinth of Night

Labyrinth of Night Galaxy Blues

Galaxy Blues A King of Infinite Space

A King of Infinite Space ChronoSpace

ChronoSpace Jericho Iteration

Jericho Iteration Captain Future xx - The Death of Captain Future (October 1995)

Captain Future xx - The Death of Captain Future (October 1995) Rude Astronauts

Rude Astronauts Arkwright

Arkwright Apollo's Outcasts

Apollo's Outcasts Coyote

Coyote Sex and Violence in Zero-G

Sex and Violence in Zero-G Avengers of the Moon

Avengers of the Moon Clarke County, Space

Clarke County, Space Time Loves a Hero

Time Loves a Hero Coyote Horizon

Coyote Horizon Orbital Decay

Orbital Decay The Last Science Fiction Writer

The Last Science Fiction Writer Tales of Time and Space

Tales of Time and Space Hex

Hex Coyote Frontier

Coyote Frontier Coyote Destiny

Coyote Destiny Lunar Descent

Lunar Descent Angel of Europa

Angel of Europa Spindrift

Spindrift Coyote Rising

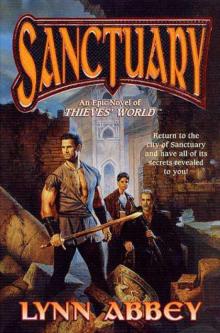

Coyote Rising Sanctuary

Sanctuary The Tranquillity Alternative

The Tranquillity Alternative The River Horses

The River Horses